They told me, smiling, “He needs to learn what pain feels like.” I was the lesson they dragged from a group home and locked into their house. I stayed quiet, counted days, survived. One night I found the videos—other kids, other “lessons,” all before me. My hands shook as I copied everything. They thought I was powerless. They never realized I was waiting for the moment the truth would finally speak louder than they ever could.

They said it like they were doing me a favor.

“He needs to learn what pain feels like.”

I was fourteen when I heard that sentence for the first time—standing in a caseworker’s office with a trash bag of clothes at my feet. The couple across the desk, Diane and Curtis Mallory, smiled like they were adopting a stray dog. Diane’s pearls caught the light every time she nodded. Curtis kept his hands folded, posture perfect, the kind of calm that makes adults assume safety.

The paperwork called it “placement.” The caseworker called them “experienced.” The neighbors later called them “saints.”

But the first night in their house, Curtis took my phone—my only connection to anyone I’d ever trusted—and said, “Rules build character.” Diane removed the lock from my bedroom door and said, “Privacy is earned.” When I asked when I could see my caseworker again, Curtis smiled and said, “When you’ve learned to appreciate what you’ve been given.”

I learned quickly what I was there for.

Not family. Not care.

A lesson.

They didn’t hit me in ways that left obvious marks. They were too smart for that. They used punishments that looked like “discipline” to outsiders: isolation, chores that never ended, meals withheld as “consequences,” sleep interrupted by “checks” that were really just reminders that I didn’t control my own body or time.

And whenever I flinched or cried or protested, Diane would tilt her head and say, softly, “See? He needs this.”

So I stayed quiet.

I stopped asking for help in a house where asking was punished. I stopped showing emotion in a house where emotion was used as evidence that I was “unstable.” I learned to count time in small, survivable units—days, then weeks, then months. I memorized patterns: when Diane drank more, when Curtis got impatient, when it was safest to be invisible.

I survived by becoming boring.

But I also noticed things.

Curtis was obsessed with documentation—“for accountability,” he said. He had cameras in the hallway “for security.” He filmed “progress updates” for the agency. He kept a locked cabinet in his office and treated it like a sacred altar.

One night, eight months in, I was cleaning the downstairs study because Diane said I’d “earned the privilege” of extra chores. Curtis was asleep on the couch, TV murmuring. Diane was upstairs on the phone.

The cabinet key was on Curtis’s ring, dangling from the side table.

My heart hammered as I slid it free.

I unlocked the cabinet.

And inside, I found a stack of hard drives labeled with dates—years before I ever arrived.

My stomach turned cold.

Because I suddenly understood the real reason they were so confident.

I wasn’t their first lesson.

I was just the latest.

I didn’t plug anything in right away.

That was the first decision that saved me.

Panic makes you sloppy. Sloppy gets you caught. And in that house, getting caught didn’t mean a lecture. It meant consequences designed to look like “discipline” if anyone ever asked.

I slid the cabinet drawer closed as quietly as I could, relocked it, and put the key back exactly where I found it. Then I forced myself to finish the cleaning like nothing had changed. I went to bed with my face calm and my mind screaming.

The next day, I waited for an opening.

It came during grocery day. Diane insisted on driving alone because she didn’t trust me in public unless Curtis was there to “manage” me. Curtis stayed home, sitting at his desk, headset on, pretending he was doing “committee work” for the foster parent association.

I watched him through the doorway while I vacuumed the hallway, timing his movements, the moments he stood up, the moments he left the room. When he finally went to the garage for something, I slipped into the office.

His computer was unlocked.

He’d assumed I was too afraid to try.

I didn’t touch the drives yet. I checked the screen first—file folders. Names. Dates.

There it was: a folder titled “Behavioral Programs.”

Under it: subfolders with first names I didn’t recognize. Each one tagged with an intake date and an “outcome” note.

My hands started shaking so badly I had to press my palms against the desk to steady them.

I opened one file.

Video.

A boy, younger than me, sitting on a chair in the same hallway I’d scrubbed the night before. Curtis’s voice behind the camera, calm and instructional. Diane’s voice laughing lightly like it was a dinner conversation.

Not graphic—just enough to show the truth: humiliation staged like “therapy,” punishment framed as “training,” kids crying while adults narrated it as improvement.

I closed the file and swallowed hard, fighting the urge to throw up.

Then I did the only thing that mattered.

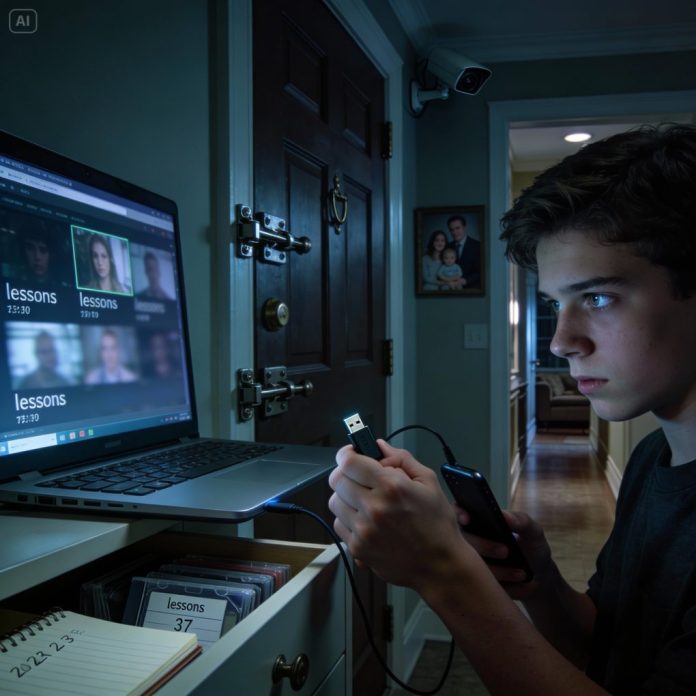

I copied everything.

Not one clip. Not one folder. All of it.

I inserted a cheap flash drive I’d stolen from a school supply bin months earlier and never used. I selected the entire “Behavioral Programs” directory and started the transfer.

The progress bar crawled.

Every second felt like a footstep behind me.

I listened for the garage door. The stairs. Diane’s car in the driveway. Anything.

The transfer hit 62% when I heard Curtis in the hallway. My blood went ice.

He paused outside the office.

I didn’t move.

He stepped away again—bathroom. I heard the sink run. Then silence.

The transfer finished.

I ejected the drive with trembling fingers, hid it inside the seam of my mattress where a rip already existed, and restored the screen to exactly what it had been.

When Diane came home, she waved a grocery bag at me and said, “Put these away. And don’t forget—consequences build gratitude.”

I nodded, face blank, hands steady.

But inside, something had changed.

Because now the truth wasn’t trapped in their house with me.

I was carrying it.

For two weeks, I lived like I was made of glass.

I didn’t give them a reason to suspect anything. I did chores. I said “yes, ma’am.” I ate when they allowed it. I kept my expression neutral even when Diane smiled and called it “progress.”

At night, when the house finally went quiet, I pulled the flash drive out and checked the files on an old school Chromebook I’d been issued—no internet access at home, but it could play local media. I watched just enough to confirm what I already knew: names, dates, the same house, the same voices, the same method.

Not a one-time mistake.

A system.

Then I waited for the one thing they couldn’t control: an outside appointment.

Curtis loved taking me to check-ins because he liked performing. He wore his “foster parent” smile, talked about how “challenging” I was, how “rewarding” it was to see me improve. Adults nodded, impressed.

On a rainy Thursday, we sat in the agency building for my quarterly review. Curtis answered questions before I could. He laughed when the caseworker asked if I felt safe. “He’s learning accountability,” he said. “He used to lie a lot.”

The caseworker, Ms. Hart, looked at me gently. “Do you want to speak alone for a few minutes?”

Curtis’s smile tightened. “There’s no need—”

“I do,” I said quietly.

The room went still. Curtis blinked like he wasn’t used to me choosing anything.

Ms. Hart led me into a smaller office and closed the door. “You can tell me anything,” she said, voice careful. “Even if you’re scared.”

I took a breath that felt like swallowing broken glass, then said, “I have evidence.”

Her eyes sharpened. “What kind?”

I slid the flash drive across the desk.

“I need you to do this the right way,” I said, voice shaking but steady. “Don’t call them. Don’t warn them. Just… watch it. And check the names.”

Ms. Hart didn’t promise miracles. She didn’t make a speech. She simply nodded once, the way serious people do when they’ve just stepped onto a line they can’t ignore.

Within forty-eight hours, I wasn’t in that house anymore.

A different caseworker picked me up. Not Curtis. Not Diane. Police were involved, but I only saw it from the backseat, through rain on the window: Curtis standing stiff on the porch, Diane crying like a victim, both of them still trying to shape the story.

They thought I was powerless because I was quiet.

They never realized I was quiet because I was planning.

And when the truth finally spoke, it didn’t sound like my voice at all.

It sounded like files, dates, and footage—things that don’t get tired, don’t forget, and don’t back down when someone smiles and says, “Be grateful.”

If you were reading this as someone who cares about kids in the system, would you want the survivor to go to a caseworker first, or to law enforcement first—and why? I’m curious, because the difference between getting saved and getting silenced is often one decision made in secret… and one person choosing to document instead of just endure.