“The alarm screamed and someone yelled, ‘Carbon monoxide—get out!’ but our biology teacher slammed the door and hissed, ‘Anyone who leaves gets a zero on the midterm.’ My head was pounding, my chest burning, and I remember whispering, ‘I don’t feel right,’ as classmates collapsed into their seats. I stayed. Minutes later, sirens wailed outside—and that’s when I realized this test might cost us more than our grades.”

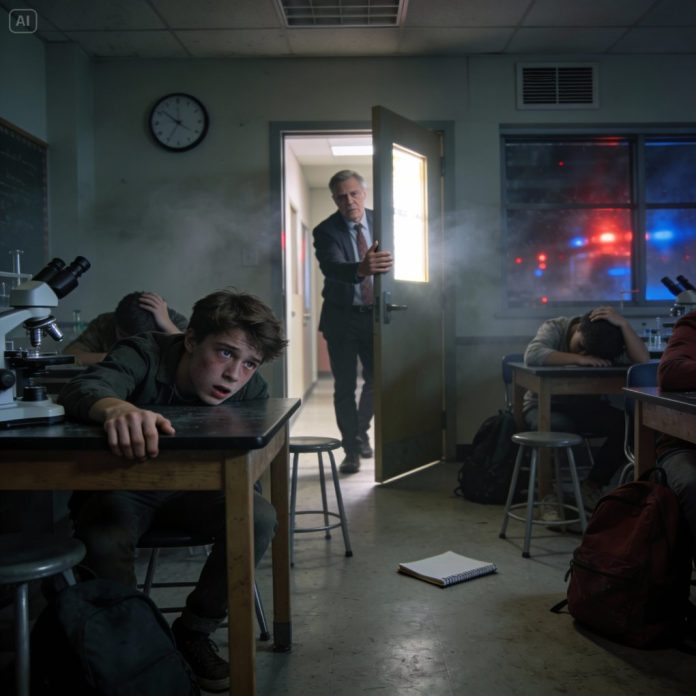

The alarm cut through the hallway like a scream, sharp and metallic, echoing off lockers and concrete walls. For a split second, everyone froze. Then someone near the door shouted, “Carbon monoxide—get out!” Chairs scraped back. A few students stood up instinctively, panic flaring across their faces.

That’s when Mr. Harlan slammed the classroom door shut.

The sound was loud enough to make us jump. He locked it, turned around, and said in a low, furious voice, “Sit down. Anyone who leaves this room gets a zero on the midterm.”

The words landed heavier than the alarm. This was our final exam week, the test that determined college recommendations, scholarships, futures—at least, that’s how it felt at seventeen. Mr. Harlan was known for being strict, the kind of teacher who bragged about how many students failed his class. He believed fear built discipline. And in that moment, fear worked.

The alarm kept blaring, muffled now but relentless. My head started to throb almost immediately, a dull pressure behind my eyes. The air felt thick, like breathing through warm fabric. Someone in the back whispered, “Is this real?” Another student laughed nervously and said, “It’s probably a drill.”

Mr. Harlan marched to the front of the room and wrote BEGIN on the board. “You have ninety minutes,” he said. “No excuses.”

I tried to focus on the test, but the letters swam. My chest burned with every breath, shallow and unsatisfying. I raised my hand halfway, then let it drop. My palms were sweaty. Across the aisle, a girl named Rachel rested her head on her desk, eyes closed. Two rows ahead, a guy slumped back in his chair, blinking hard like he was fighting sleep.

“I don’t feel right,” I whispered to the student next to me. He didn’t answer—just stared at his paper, jaw clenched, pencil shaking.

The alarm finally stopped, replaced by an eerie quiet that made the room feel sealed off from the rest of the world. Mr. Harlan smiled thinly, as if order had been restored. “See?” he said. “Nothing to worry about.”

That was when Rachel slid out of her chair and hit the floor.

Her body made a dull sound against the tile. Someone screamed. Another student stood up, swaying, and grabbed the edge of a desk to stay upright. My vision narrowed, black creeping in from the corners. Through the haze, I heard distant sirens—faint at first, then unmistakable.

And as the sound grew louder, one thought cut through the fog in my head with terrifying clarity: this test might cost us more than our grades.

Everything unraveled at once.

The classroom door burst open, forced from the outside by a vice principal whose face was flushed with panic. “Evacuate now!” she yelled. “Everyone out—now!”

Mr. Harlan started to protest. “They’re in the middle of a—” but he was cut off by a firefighter in full gear pushing past him, shouting for us to move. The authority in that voice broke whatever spell had held us in our seats.

I tried to stand and nearly fell. My legs felt like rubber, disconnected from my brain. Two classmates grabbed my arms and half-dragged me into the hallway, which was filled with coughing students, teachers shouting directions, and the sharp, chemical smell that made my eyes sting.

Outside, the cold air hit my lungs like a shock. I dropped to my knees on the pavement, gasping, my head spinning violently. All around me, students were sprawled on the grass or sitting hunched over, hands on their heads. Paramedics moved fast, checking pulses, fitting oxygen masks over faces that looked pale and dazed.

Rachel was loaded onto a stretcher, unconscious. The guy who had been slumped in his chair was vomiting into a bag, his hands shaking uncontrollably. Someone else started crying—not loud, hysterical sobs, but quiet, broken sounds that scared me more.

A paramedic knelt in front of me and asked, “How long were you exposed?”

I didn’t know how to answer. “The whole test,” I said finally. “We weren’t allowed to leave.”

Her eyes flicked toward the building, sharp and angry. “You’re lucky,” she said. “This could’ve been a lot worse.”

We learned later that a malfunctioning boiler had been leaking carbon monoxide into one wing of the school. Other classrooms had evacuated immediately. Only ours stayed.

Mr. Harlan was taken aside by administrators. He didn’t look angry anymore. He looked small. Pale. Like someone who had just realized the weight of a decision he couldn’t undo.

Several students were hospitalized overnight for carbon monoxide poisoning. Parents flooded the school, furious and terrified. The midterm was canceled, of course—quietly, like it was an afterthought. No grade mattered now.

That night, lying in a hospital bed with an oxygen tube under my nose, I kept replaying the moment my hand dropped back to my desk. The moment I stayed seated when every instinct told me to run. I hadn’t been physically restrained. The door hadn’t been locked to keep us safe—it had been locked to keep us obedient.

And obedience, I realized too late, had almost killed us.

The school district called it “a serious lapse in judgment.” That was the phrase used in the official letter sent home to parents. Mr. Harlan was placed on administrative leave, then quietly removed from teaching the following semester. No criminal charges. No dramatic courtroom reckoning. Just a job that ended and a story that faded—except for those of us who were in that room.

Rachel transferred schools. She still gets migraines, last I heard. A few students developed anxiety whenever alarms went off—fire drills, car alarms, even microwave beeps. As for me, I learned something that day no textbook ever taught me.

Authority does not equal safety.

We’re trained early to obey teachers, bosses, supervisors—people who control our grades, our paychecks, our futures. And most of the time, that trust is reasonable. But when rules collide with survival, the rulebook should burn.

Carbon monoxide is invisible. It doesn’t roar or smell like danger. It just steals your clarity, your strength, your ability to argue back. That’s what made that classroom so terrifying in hindsight—we were being poisoned and pressured at the same time. Even as our bodies warned us, our training told us to sit still.

I think about how easily this happens outside of schools too. In workplaces where people are told to “push through” dizziness, pain, exhaustion. In hospitals where junior staff hesitate to challenge senior doctors. In everyday moments when someone says, “It’s probably nothing,” and everyone else swallows their doubt.

If you’re reading this and you’re in a position of authority, remember this: your words carry weight even when you’re wrong. Especially when you’re wrong. And if you’re the one sitting in the chair, heart pounding, lungs burning, thinking something isn’t right—please hear this clearly.

You are allowed to leave.

You are allowed to protect yourself, even if someone in charge tells you not to. A grade can be retaken. A job can be replaced. A life cannot.

If you’ve ever ignored your body because someone else told you to, or if you’ve ever been punished for choosing safety, share your experience. Talk about it. Stories like this only matter if they travel—if they reach the next person sitting in a room, hearing an alarm, wondering whether they’re allowed to stand up.

Because sometimes, the most dangerous test isn’t on the paper in front of you. It’s whether you’ll trust your instincts when it matters most.