After my mother moved into our house for home care, I told myself it would be hard—but manageable. She seemed quiet, fragile, almost harmless.A few days later, my daughter tugged my sleeve, eyes wide, voice shaking. “Mom… something’s wrong with Grandma.”I tried to laugh it off. “She’s just adjusting,” I said—until I noticed my daughter wouldn’t go near that hallway anymore.The next morning, we waited until the house was silent. Then we crept to my mother’s door and pushed it open—just a crack.And what we saw inside made our bodies lock up in pure fear.

We couldn’t even speak.

Emma Caldwell told herself she could handle it.

When her mother, Diane, was discharged from the rehab facility and needed home care, Emma and her husband, Jason, agreed to convert the small guest room at the end of the hallway into a comfortable space. They moved in a recliner, a nightstand, extra lamps, a baby monitor—more for safety than surveillance—and a basket of easy snacks. Diane arrived with a single suitcase, quiet and pale, her hair brushed neatly as if she were going somewhere formal instead of moving into her daughter’s home.

For the first few days, she seemed fragile. Almost harmless. She spoke softly, thanked Emma too often, and spent long hours in her room with the door mostly closed. Emma tried to see it as grief and adjustment. Her mother had lost her independence. She was embarrassed. She needed time.

Then Emma’s nine-year-old daughter, Sophie, began hovering closer than usual.

Sophie was usually fearless—loud, curious, the kind of kid who would wander into any room without knocking. But now she stayed near the kitchen, near the living room, anywhere not near that end of the hall.

On the fourth night, as Emma loaded the dishwasher, Sophie tugged her sleeve. Her fingers were cold.

“Mom,” Sophie whispered, eyes wide and wet, “something’s wrong with Grandma.”

Emma forced a small laugh, trying to keep her tone light. “Sweetheart, she’s just adjusting. She’s had a hard time lately.”

Sophie shook her head fast. “No. It’s… she does things.”

“What things?” Emma asked, still smiling, still trying to make it normal.

Sophie’s voice dropped to almost nothing. “She whispers in my room when you’re asleep.”

Emma froze for half a second, then pushed it aside with the logic adults use to protect themselves. “Maybe you had a dream. Or you heard the TV.”

Sophie’s lower lip trembled. “I wasn’t dreaming.”

That night, Emma watched Sophie avoid the hallway like it was hot. If Sophie needed the bathroom, she asked Emma to come with her. If Sophie dropped a toy near the hall entrance, she waited until Jason walked by and asked him to pick it up.

Emma caught herself getting irritated—then guilty—then uneasy.

The next morning, Sophie didn’t want to go to school. She clung to Emma’s sweater and begged to stay home. Emma finally relented, telling herself she’d call the nurse and ask for advice about Diane’s medications. Maybe they were causing confusion. Maybe Diane was sleepwalking.

But when the house finally went quiet—Jason at work, the visiting nurse not due until noon—Sophie looked up at Emma with a seriousness that didn’t belong on a child’s face.

“Can we check?” Sophie whispered. “Please.”

Emma hesitated, then nodded. She didn’t know what she expected to find—maybe Diane asleep, maybe a mess, maybe nothing at all.

They walked down the hallway together, their steps careful on the hardwood. Diane’s door was closed. The air felt colder there, as if the rest of the house stopped breathing.

Emma placed her hand on the knob and turned it as gently as she could. The latch clicked.

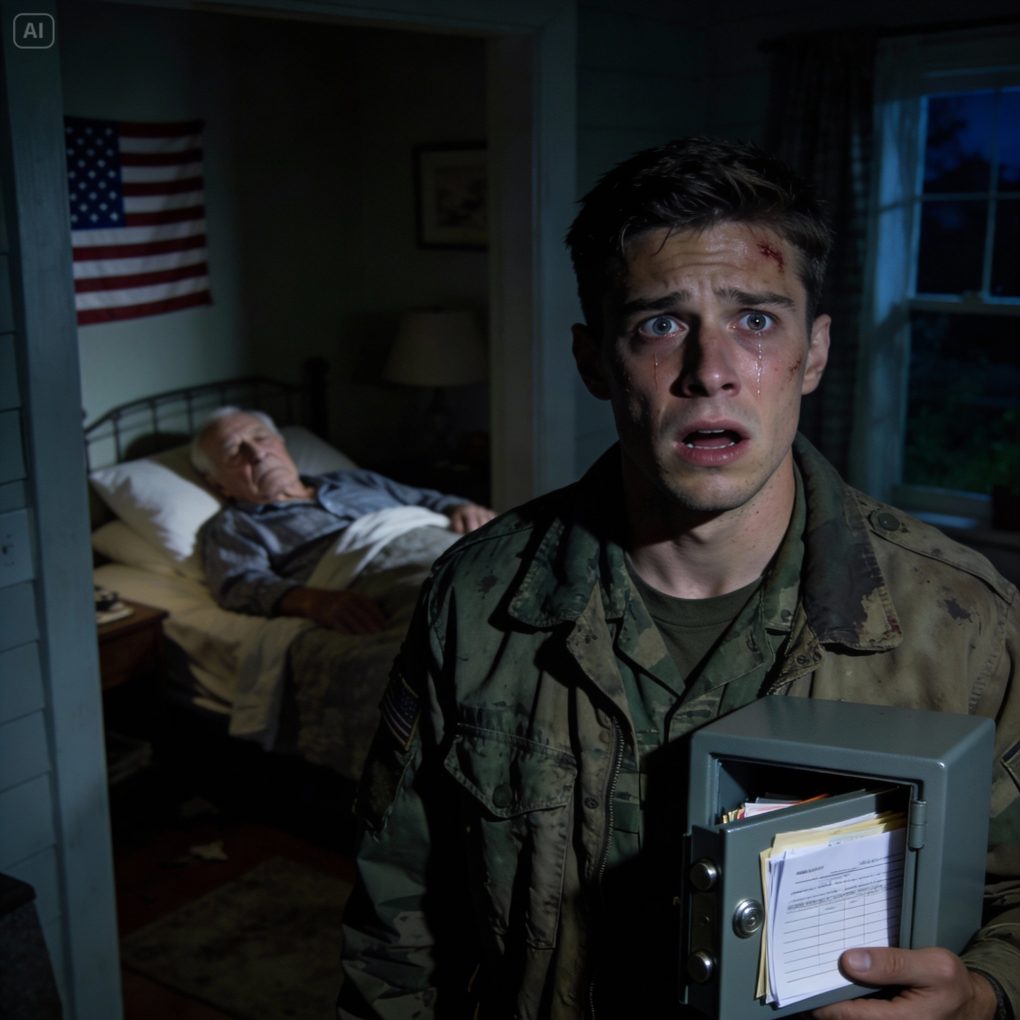

They pushed the door open—just a crack.

And what they saw inside made both of their bodies lock up in pure fear.

Emma’s throat closed. Sophie’s fingers dug into her arm.

They couldn’t even speak.

At first, Emma’s brain refused to label what she was seeing.

Diane wasn’t in bed.

She was standing in the middle of the room, perfectly still, dressed like it was daytime—cardigan buttoned, shoes on, hair smoothed back. The curtains were pulled shut. The lamp was off. The only light came from the thin gray strip under the blinds, turning the room into a dim box.

And Diane was facing the wall.

Not like someone lost in thought—like someone listening.

Emma’s hand tightened on the door edge. “Mom?” she whispered, not wanting to startle her.

Diane didn’t turn.

Then Emma noticed the floor.

There were rows of objects arranged with obsessive care—Sophie’s things. A hair clip shaped like a butterfly. A bracelet Noah had made at summer camp. A tiny sock. Two crayons. A small stuffed rabbit Sophie had “lost” the day before. They were placed in neat lines, spaced evenly like evidence on a table.

Sophie made a small choking sound behind Emma.

Emma’s heart began to slam. “Where did you get those?” she asked, voice sharper now.

Diane’s shoulders rose slowly, as if she were inhaling. Still she didn’t turn. “They leave them everywhere,” she said, voice calm. “Children should learn.”

Emma’s stomach rolled. “Those are not yours. You took them from my daughter.”

At that, Diane finally moved—turning her head just enough for Emma to see her profile. Her expression wasn’t confused. It wasn’t foggy or medicated.

It was controlled.

“You let her walk past my door at night,” Diane said softly. “She watches. She listens. She’s nosy.”

Sophie whimpered. “I don’t— I don’t go there.”

Emma stepped into the room without thinking, positioning herself between Sophie and Diane. “Sophie doesn’t come here,” Emma said. “And even if she did, you don’t take her things. You don’t go into her room.”

A faint smile pulled at Diane’s mouth. “I don’t go into her room,” she said. “She comes to me.”

Emma’s skin prickled. “That’s not true.”

Diane’s eyes flicked toward Sophie—quick, assessing—and Sophie flinched so hard Emma felt it through their linked arms.

“Tell her,” Diane said to Sophie, voice sweet. “Tell her you come. Tell her how you stand in the hall.”

Sophie started shaking her head, tears spilling. “No. No. You— you come by my door. You whisper. You say I’m… bad.”

Emma’s blood went icy. “What did you say to her?”

Diane’s smile widened a fraction. “I’m helping. Someone has to.”

Emma grabbed the stuffed rabbit off the floor. Her hands were trembling now, not from confusion but from rage. “This stops today,” she said. “You will not speak to my daughter like that again.”

Diane tilted her head. “You’re overreacting.”

But there was something else in the room that made Emma’s breath catch—something that didn’t fit the “strict grandma” story. On the nightstand, beside Diane’s pill organizer, was a small notebook, open to a page filled with writing. Not diary writing—lists. Columns. Times. Notes.

Emma stepped closer, eyes scanning:

Sophie — 9:12 p.m. hallway

Sophie — 1:03 a.m. whispering stopped

Sophie — 6:40 a.m. bathroom, looked scared (good)

Emma’s mouth went dry.

This wasn’t adjustment.

This was fixation.

And it had already been happening while Emma was asleep.

Emma didn’t argue anymore. She didn’t try to reason with her mother, because the notebook on the nightstand said everything Diane’s calm voice was trying to hide.

Emma backed out of the room slowly with Sophie glued to her side. She shut the door without slamming it—instinctively, like you don’t provoke something unpredictable when you’re not sure what it is.

In the kitchen, Emma locked the back door and pulled Sophie onto a chair where she could see the hallway entrance. She handed her water with shaking hands.

“Sweetheart,” Emma said softly, “I believe you. Okay? You did nothing wrong.”

Sophie sobbed so hard her shoulders shook. “She said if I told you, you’d send her away and it would be my fault.”

Emma’s chest tightened with a rage so clean it felt like steel. “No,” she said firmly. “This is not your fault. This is my job. I’m the mom. I handle grown-up problems.”

Emma called Jason at work. The moment he heard Sophie crying in the background, his voice sharpened. Emma told him what they saw, keeping it factual—objects lined up, the notebook, the “whispering,” the way Diane looked at Sophie like she was studying her.

Jason didn’t hesitate. “I’m coming home,” he said. “Right now.”

Next, Emma called the visiting nurse service and asked for an urgent supervisor visit. She didn’t say “my mother is evil.” She said what professionals understood: “Behavioral changes. Boundary violations. Child feels unsafe. Documentation suggests obsessive monitoring.”

The nurse supervisor arrived within an hour, and Emma showed her the notebook. The woman’s face tightened as she read the timestamps.

“This is concerning,” the supervisor said carefully. “It could be medication-related confusion, delirium, or early cognitive decline with paranoia. But regardless of the cause—your child’s safety comes first.”

Emma nodded, throat burning. “What do I do?”

“You need to separate them immediately,” the supervisor said. “And I recommend an emergency psychiatric evaluation through her physician or the hospital, especially if she’s displaying fixation or threatening language.”

When Jason got home, they made a plan in the simplest terms possible: Sophie would stay with Jason’s sister for a few days. Emma would not be alone in the house with Diane. And Diane would not stay in the guest room another night.

Emma knocked on Diane’s door with Jason beside her. “Mom,” Emma said, voice steady, “a nurse is here to assess you. We’re also arranging a higher level of care.”

Diane opened the door halfway, eyes cool. “You’re sending me away,” she said, like it was a test.

“I’m protecting my child,” Emma answered.

For the first time, Diane’s composure slipped—just a flicker of anger, then a quick return to sweetness. “After everything I did for you,” she whispered.

Emma didn’t take the bait. She looked at her mother and understood something painful: love doesn’t erase harm, and family doesn’t earn unlimited access.

That evening, as Sophie hugged Emma goodbye at the car, Sophie whispered, “Are we safe now?”

Emma kissed her forehead. “We will be,” she promised—because safety wasn’t a feeling, it was a decision.

If you were Emma, what would you do next: insist on a hospital evaluation immediately, move Diane to a facility right away, or involve child protective services/police because of the stalking-like notes? Tell me which option you’d choose and why—your perspective might help someone reading this recognize the line between “struggling” and “unsafe.”